Tags

Alicia Markova, American Ballet Theatre, Ballet of the Elephants, Ballets Russes, Bronislava Nijinska, Circus and the City: New York 1793-2010, Discovery.com, George Balanchine, George Benjamin, Henri Matisse, Igor Stravinsky, Matthew Wittman, Picasso, RIngling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus, Sergei Diaghilev, The Firebird, The Jewish Museum, The Rite of Spring, Vaslav Nijinsky, Vera Stravinsky

No one said breakthrough art is easy, either for the creator or the initial audience. When Igor Stravinsky composed The Rite of Spring (Le Sacré de Printemps) for the Ballets Russes 100 years ago, it spearheaded a revolution in contemporary music – and a revolt in the theatre. Ballet patrons physically rioted when faced with the cacophonous score accompanying Vaslav Nijinsky’s equally provocative choreography. Though police were called in, impresario Sergei Diaghilev couldn’t have been happier. The more his ballet company shocked, the more press he got, and the more tickets he sold.

“No composer since can avoid the shadow of this great icon of the 20th century, and score after score by modern masters would be unthinkable without its model,” British composer George Benjamin wrote of Stravinsky in The Guardian this past May. “This, in a way, is cubist music – where musical materials slice into one another, interact and superimpose with the most brutal edges, thus challenging the musical perspective and logic that had dominated European ears for centuries.”

Diaghilev was a genius at choosing artists who challenged the status quo. Who but the avant-garde Russian would have asked Picasso to create cubist ballet costumes – out of stiff cardboard no less!

– or applaud Bronislava Nijinska’s startling surrealist make-up for Léonide Massine’s Kikimora in 1917?

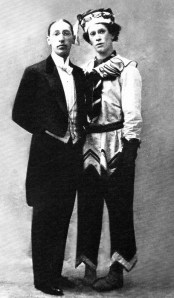

When Diaghilev invited Alicia Markova to join the Ballets Russes as its youngest-ever soloist in 1923, she was a shy, unsophisticated 14-year-old. (See photo below.)

Her first starring role was in Le Chant de Rossignol (The Song of the Nightingale), with choreography by George Balanchine – his first major commission for Diaghilev – and music by Igor Stravinsky. While the tiny dance prodigy had no problems mastering Balanchine’s complicated and supremely athletic dance sequences, Stravinsky’s music was another matter. As Markova reminisced in The Making of Markova: I remember the very first rehearsal with Balanchine. I started to cry and they said what’s the matter? I said I’m never going to be able to learn this. You know, this isn’t music to me. What am I to do? And Stravinsky was so wonderful. . . . He said, “There’s no worry. I’ll be there for all the rehearsals, and I will conduct, [unheard of for the celebrated composer!] and as long as I’m here, you mustn’t worry, but there’s one thing you have to promise me . . . You’ve got to learn the scores by ear. You must learn the instrumentation, orchestration and everything by ear,” he said, “and then you’ll never have any worry for the rest of your life.” And he was so right.

Not only did Stravinsky become Markova’s music instructor, but he accompanied her, Diaghilev, and Henri Matisse (the lucky Alicia’s art teacher!) to the studio of Nightingale costumier (and former ballet dancer) Vera de Bosset Soudeikine, who incidentally, would become Stravinsky’s second wife. Matisse was responsible for Markova’s costume design, with Mme. Soudeikine charged with bringing his creation to life.

Stravinsky happily married to second wife Vera de Bosset Soudeikine, both subjects (along with Balanchine), of Richard Nelson’s fascinating play Nikolai and the Others, performed at Lincoln Center last spring.

When Matisse announced his plan to cover Markova’s little girl hair bob with a white bonnet trimmed in osprey feathers – an extravagantly expensive trim – the budget-minded Diaghilev emphatically cried ‘No!” As Markova finishes the story in The Making of Markova: But please Sergevitch,” pleaded Matisse, “the little one needs them round her face to soften the hard line of the bonnet and make her a little bird,” protested Matisse. “No ospreys,” repeated Diaghilev. Then Stravinsky entered the argument. He too thought they were necessary, but Diaghilev was adamant and refused, and unexpectedly Stravinsky turned to Matisse and said, “Henri, we buy the ospreys between us, 50-50, yes?” “Yes!” echoed Matisse, and so I had my ospreys, and how I guarded them, as if they were gold.

While Markova never again had trouble with Stravinsky’s unique musical phrasing, others were not so lucky, as when the composer collaborated again with Balanchine in New York in 1942. The mystified dancers? Pachyderms at the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus! As Matthew Wittman explained in Circus and the City: New York 1793-2010: “‘The Ballet of the Elephants’ production was an attempt by John Ringling North to bring high culture into the circus and featured fifty elephants in pink tutus accompanied by female dancers. The rhythm changes in Stravinsky’s Circus Polka proved difficult for the elephants to grasp, and it was only performed intermittently.”

Evidently pigeons and songbirds don’t care much for Stravinsky’s dissonant compositions either, according to a research study posted on Discovery.com. The classical cadences of Bach are more to their liking. Fish, it appears, are musically non-judgmental – if listening to either composer’s music results in more food.

The very human Markova, however, was an ardent and vocal Stravinsky fan – of both the man and his exhilarating music. The two remained lifelong friends and visited each other often in the United States where Stravinsky moved with Vera during World War II.

Markova asked Stravinsky to compose music for her Broadway debut – to which he happily consented – and she delighted starring at the Ballet Theatre (today’s American Ballet Theatre) in the 1945 revival of The Firebird, the composer’s first commission for the Ballets Russes back in 1910. (Though Michel Fokine choreographed the ballet for Anna Pavlova, she refused the role proclaiming Stravinsky’s music “noise!”) Marc Chagall (currently the subject of a illuminating new exhibit at The Jewish Museum in New York) designed Markova’s breathtaking Firebird costume, which was covered in shimmering gold dust and topped with a dramatic headdress of bird of paradise feathers. One wonders if osprey plumes were still just too expensive!