Tags

Aleko, Alexandra Danilova, Alicia Markova, Anton Dolin, Ballet in a Boxing Ring, Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, Capezio, Cebu, Hollywood Bowl, Leonide Massine, Marc Chagall, Markova-Dolin Company

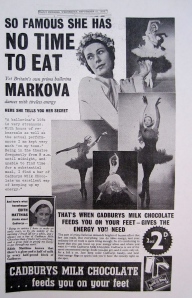

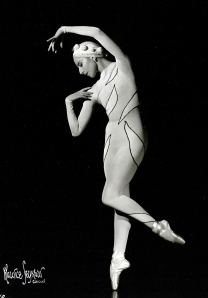

Oh, to be famous and travel the globe performing! Sounds so thrilling. And it was a thrill ride for the universally acclaimed Alicia Markova, but not one most people would sign up for. International ballet tours in the 1940s were far more grueling than glamorous, often involving dangerous locales, ghastly heat and humidity, and warped stages with gaping holes.

For Markova, it was all an adventure. She would become the most widely traveled dancer of her generation – often under her own steam, without monetary or management support from a major company – willing to sacrifice comfort and security in order to bring ballet to everyday people everywhere.

Easy this was not, especially in tropical heat. For anyone suffering through a scorching August day, picture having to wear tights, a multi-layered tutu, and dance for two hours!

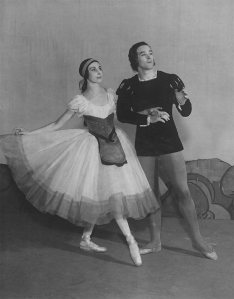

And that was often just the beginning of a dancer’s trials. Take Markova’s first trip to South America, where temperatures could reach 120 degrees and air-conditioning in theaters was unheard of. It was 1940 and she had the good fortune to be co-starring at the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo with her best friend, the vivacious prima ballerina Alexandra Danilova.

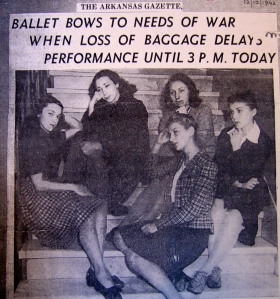

After completing an arduous cross-country US tour in New York, the company was preparing for their international booking when a doctor arrived at rehearsal to administer vaccinations.

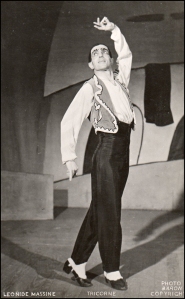

Artistic director Léonide Massine insisted that needles go into the dancers’ left legs rather than arms, so if any unsightly skin reaction erupted, tights would provide cover. Markova disagreed, as she had experienced problems with shots in the past and her legs were her livelihood. Massine won the argument. From The Making of Markova:

Danilova and Markova were booked in a “first class” cabin, which they soon discovered was “the size of an average broom cupboard.” The close quarters would seem even more so as the boat went farther and farther south and the weather got increasingly hot and humid.

About ten days into the trip, Markova’s leg began to swell, eventually ballooning to twice its normal size. The ship’s doctor insisted that she lie still the entire trip with her leg elevated while he attempted to treat the inflammation with various dressings. But the swelling only got worse, hardened and eventually went numb. “I had a left wooden leg. It was like a piano leg,” Markova remembered.

. . . As the ship got closer to landing in Rio de Janeiro, a long list of warnings was issued to the company prior to disembarking. Markova’s stiff leg seemed to pale in comparison. Drinking plenty of bottled water with salt tablets was standard enough advice, but they were also told to avoid alcohol at bars, as local café glasses were known to spread syphilis of the mouth. If that wasn’t dismaying enough, the pretty young corps members were cautioned never to go out alone, as white slavery was a thriving business. Welcome to Rio!

. . . There was just one day to practice before opening night when Markova was scheduled to perform an excerpt from Swan Lake. Wouldn’t you know – that particular scene was danced almost entirely on the left leg. “[T]he heat was agony,” she remembered quite clearly. “I suffered really quite a few days after we were there with that leg.” Though the tights masked her wound, they only made her feel hotter.

The rest of the company wasn’t faring much better. Despite all the health warnings, one after another the dancers fell ill from dysentery, heat prostration, and various other ailments. . . . One evening Markova had to dance the demanding leads in two lengthy ballets and, upon leaving the stage after the final curtain, fainted from exhaustion in the wings.

Dolin and Markova had as much luck fishing in Cuba as they did dancing on a horribly warped stage. At least they had time for lunch with Ernest Hemingway.

Bigger problems than intense heat awaited Markova when she returned to Central and South America in 1947, this time with her Markova-Dolin Company co-founded with longtime partner – and fellow Brit – Anton Dolin.

Again, from The Making of Markova: In Bogota, the British consulate left word that the company was not to leave the hotel, as “there is going to be shooting today.” Only one matinee and evening performance were cancelled. Apparently they were all done shooting the next morning. A sudden revolution also prevented Markova and her partner Anton Dolin from a quick stopover in Nicaragua to dine with an old friend. “So we missed luncheon and the possibility of a bullet in the hors d’oeuvre,” Markova humorously recalled.

The stage was in such bad shape in Cuba, Markova feared her “Dying Swan” might literally live up to its name.

But it was in Cuba that Markova danced on the worst stage of her career – and that’s saying something. She had already maneuvered around holes, slippery marble, sharp tilts, and squished flowers, but the Cuban floorboards were a veritable roller coaster. Due to the incessant heat and humidity, the wood was so warped that it looked more like a Mediterranean tile roof than flooring.

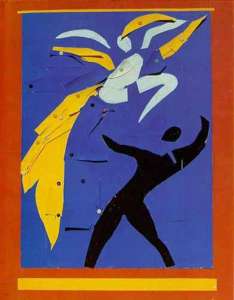

When it came to her personal wardrobe, Markova quickly learned how to pack light and deal with extreme heat while touring. Shopping trips with celebrated modern artist Marc Chagall and his wife proved especially fruitful. The three were in Mexico City in 1942 preparing for Massine’s new ballet Aleko. Commissioned to create the sets and costumes, Chagall produced such astonishingly beautiful designs that they were applauded as loudly as the dancing. (To view those remarkable designs, see my former post “The Colorful Marc Chagall.”) From The Making of Markova:

Perhaps inspired by her Giselle costumes, Markova had lightweight peasant blouses and dresses designed for tours in extreme heat.

“I used to go to the market with Chagall often, and in Mexico at that time, it was very primitive,” Markova later recalled. “You could go to the market and buy all the wonderful cotton materials, and they were all dyed – by the Indians you see – in these fantastic colors. Well, they were almost psychedelic colors: the marvelous candy pinks, and yellow, and oranges. You could choose your materials and choose the lace and everything, and the braids, and design your own, what you had in mind, and then you brought it and you took it to the other end of the market.”

There a “little lady in black” sat at a Singer sewing machine and Markova would show her what she had brought and present her design ideas. Since the fabrics were so cool and lightweight, the ballerina thought them ideal to wear while on tour in stifling climates.

Rather than shop for themselves, the Chagalls used the outdoor marketplace as an inspiration laboratory for costume design; and they too would buy fabrics, intricately cut lace, and decorative trim for the elderly seamstress to stitch up to specifications. (Of course, it was Chagall’s hand painting on the fabrics that made the costumes true works of art.)

When the company later performed Aleko in Los Angeles in July of ’43, the lightweight costumes proved little salvation in oppressive weather conditions. “Dancing in the humid air five nights a week, after rehearsing through a hot, sunny day at the Hollywood Bowl, or in one of the airless dance studios, was having its effect,” recalled Anton Dolin. Even more of an issue was Massine’s diabolically difficult choreography which had felled several dancers in rehearsals. The afternoon of the Hollywood premiere, Markova so severely pulled a muscle that she passed out cold; but with a sold-out crowd of 35,000 for opening night, she had no choice but to go on.

From The Making of Markova: The program went on as scheduled and Markova gave her normally fiery performance until almost the end of the ballet. Suddenly she felt a stabbing pain that she just couldn’t dance through and dropped to the stage. Co-star Hugh Laing immediately carried her into the wings and an ambulance was called. Another ballerina quickly took Markova’s place to finish the ballet, which at that point, required only that she be stabbed to death by Laing’s Aleko. But the audience barely paid attention. They were all murmuring about what had happened to Markova.

She would be out of commission for the rest of the summer.

By the time Markova and Dolin flew to the bombed-out Philippines in ’48 – a journey so daunting the pair were the only two dancers on the trip – she was an experienced packer for all kinds of weather. Even so, a surprise awaited her in Hawaii – a mid-point booking scheduled to break up the lengthy trip. (In those days it took 4 days just to fly from Hawaii to Manilla!) Despite all her preparations for the tropics, Markova was shocked at how much her feet swelled from the combined heat and humidity. She could barely fit into her ballet shoes. Worse still, the blocking in the toe turned to complete mush. From The Making of Markova:

A panicked telegram was immediately dispatched to Capezio in New York, where all of Markova’s ballet shoes were hand-made, requesting that the company quickly send a dozen new pairs a half-size larger, lighter weight, and with sturdier toe blocks. The shipment arrived well before the departure for the Philippines. Never again would Markova attempt such a trip without a supply of what she now called her “tropical” toe shoes.

The beautiful native Manila costumes worn by the two dancers sharply contrast with the wartime building devastation behind them.

[Awaiting Markova and Dolin in the Philippines was unimaginable devastation: miles of strewn rubble, bombed-out buildings, and a strong military presence.] First on the agenda was checking into the Manilla hotel – or half a hotel, as it turned out. “I remember opening a door next to my suite, which led directly and terrifyingly on to nothingness; the rest of the building had been sheared away by bombing,” Markova wrote in her memoirs. At the hotel’s front desk was the sign PARK YOUR FIRE-ARMS HERE – a none-too-reassuring reminder of daily shootings.

[It hardly mattered. The Filipinos could not have been more gracious or appreciative that the famous dancers had made the dangerous, arduous trip. No dance company had visited the Philippines since Anna Pavlova in 1924, and huge crowds gathered for every performance, many in outdoor fields in the middle of nowhere.] When Markova arrived in Cebu, she was taken to the barren outdoor cinema where she and Dolin would dance that evening. The locals were transforming the site right before their eyes.

For a stage, dozens of upturned lemonade cases were lashed together and covered with a canvas. Off to one side sat a group of Filipino women, who one by one were cutting open old military grain sacks. The flattened fabric was then stitched together and painstakingly decorated with hundreds of wild tuberoses. It was a unique and quite beautiful backdrop. On the other side of the makeshift stage were placed several drained gasoline drums, now filled with fragrant flowers. The scent was so overwhelming, Markova remembered, as if someone had spilled bottles of expensive perfume everywhere.

. . . The entire audience was hypnotized. Every time Markova rose up on her toes, there was an audible gasp. No one could imagine how that was humanly possible. The rapturous reception was the same all over the Philippines, bringing as much joy to the dancers as the worshipful crowds. [For the story of Markova’s performing on another unusual stage in Manila, see my former post “Ballet in a Boxing Ring? It was a knockout!”]

While on tour, Markova loved visiting local ballet schools, as here in Manila, to encourage her passion for dance.

Markova and Dolin also made time to visit one of the local ballet teachers, helping her to develop easy-to-master lesson plans for her newly star-struck dance students.

Before the trip, Dolin wasn’t initially keen on such a grueling journey, but Markova talked him into it. “Whenever people say to me, ‘Oh, you can’t go to a certain place because there is no theater there or there isn’t any public,’ I would always say to Pat [Dolin], that’s where we’re going because it must be opened up.”