Tags

"Necessity is the mother of invention.", Agnes DeMille, Al Hirschfeld, Alice Nikitina, Alicia Markova, Anna Pavlova, Anton Dolin, Arnold Haskell, Ballet Club, Ballet Russes, Beatrice Lillie, Bernard Williams, Bert Lahr, Cyril Beaumont, Frederick Ashton, George Balanchine, Jacob's Pillow, John Drummond, John Rawlings, La Chatte, La Péri, leg warmers, London's Regal Cinema, Marie Rambert, Mark Twain, Maryinsky Ballet School, Mercury Theatre, Olga Speeivtseva, prima ballerina assoluta, Radio City Music Hall, Sergei Diaghilev, Speaking of Diaghilev, The Nightingale, The Seven Lively Arts, Vogue, wartime rationing

Ironically, no one knows for sure who “invented” the adage “Necessity is the Mother of Invention.” Though variously attributed to Plato, Aesop, and an Indian philosopher (no, it wasn’t Frank Zappa), the saying came into general usage in 17th century England. Several hundred years later, the proverb would prove prophetic for a small, sickly Jewish girl from Finsbury Park, London. Born in 1910 with flat feet, knock knees and weak legs, Lilian Alicia Marks was the unlikeliest of future ballet stars. First, all classical ballerinas in her day were Russian. Second, as Markova herself often joked, “What would people say to a girl with throat trouble who announced her intention of becoming an operatic singer?”

It was at the beach that Eileen Marks first noticed her daughter’s “duck-like” flat feet, knock-knees and wobbly legs. (Pictured here: the 5-year-old Markova next to her mother holding baby sister Doris.)

And indeed, little Lily would never have dreamt of a dance career had ballet class not become a necessity. Not only did she have fallen arches, but her right knee often buckled under. The doctor proposed leg irons as a cure, a fate neither the frail seven-year-old nor her mother relished. Any other options? Ballet exercises might strengthen her limbs and feet, offered the physician. They did. And a ballet prodigy was discovered in the process.

Mark Twain’s variation on the theme was “Necessity is the mother of taking chances.” That was certainly true when the painfully shy Lily Marks, age 13, auditioned for Ballets Russes impresario Sergei Diaghilev and his new hire – the untried choreographer George Balanchine.

From the The Making of Markova: “Balanchine started asking me to do all kinds of things, including a lot of acrobatic steps. These I did rather to his surprise, mine too I might add. Finally he said, ‘Now please do for me two pirouettes in the air, like the men do.’ This seemed to me a little extraordinary as I had never even tried to do one. Anyway, I attempted it and went round perfectly. He was delighted and said, ‘Yes, you will do.'”

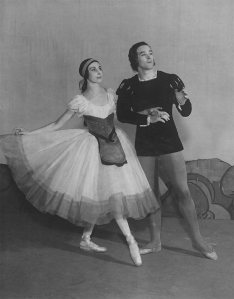

George Balanchine asked the teenaged Markova to do acrobatic steps formerly only performed by men. Their collaboration on The Nightingale was a triumph for them both.

Within months, the naïve teen became the youngest ever soloist at the world famous Ballets Russes and star of Balanchine’s first full-length choreographic work for the company, The Nightingale. As London newspaper The Independent would later comment: “Alicia’s incredible virtuosity thrilled Balanchine. He included double tours en l’air, a turning jump from the male lexicon, and devised a diagonal of jouettés that gave the impression of a little bird hopping.” The ballet launched both of their careers. However, Lilian Alicia Marks would not be listed on the program. Being a prima ballerina in the 1920s “necessitated” a Russian name. “Who would pay to see Marks dance?” scoffed Diaghilev, who quickly rechristened her Alicia Markova.

Diaghilev also believed the best ballerinas made as little noise as possible. More than anything, his youngest-ever prodigy wanted to please him, so Markova learned to dance silently. “If Markova springs like a winged fairy, she comes to the ground just as lightly,” wrote British dance historian Cyril Beaumont, “noiselessly in fact, always passing – ball, sole, heel – through the whole of the supplanted foot. Of how many ballerine can that be said?”

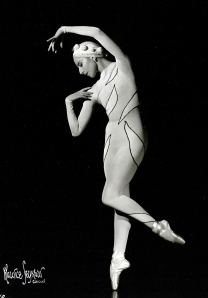

An airy lightness would become Markova’s signature, along with her never showing any signs of physical exertion or heavy breathing. She developed that otherworldly quality out of necessity when performing with Marie Rambert’s Ballet Club, one of England’s first classical dance companies in the early 1930s. “The stage at the Mercury Theatre, it was very small,” explained Rambert. “But she [Markova] turned it to her advantage. She developed a very effortless technique. You could stand quite close to her. You didn’t hear her breathe. You didn’t hear her move a step. She just floated on a cloud. It was really wonderful!”

Close proximity to audiences in a tiny theater necessitated Markova’s mastering a silent, effortless dance technique. (At the Ballet Club, 1933)

To prevent her headpieces from moving while on-stage, Markova glued them to her head! (From Cimarosiana, 1927.)

Markova may have been extremely timid off-stage in her early dancing years, but she was a whirlwind on. So much so, that one night while doing a series of rapid turns, her headdress flew off, fortunately settling ’round her neck rather than landing with a thud. Though Diaghilev was impressed she kept dancing impeccably, he sternly warned that must never happen again. The obedient teen’s solution? Glue. Fortunately she found one that stuck without removing every hair on her head.

Nicknamed “the Sphinx” by her Ballets Russes peers, Markova was exceptionally quiet in a company of exuberant personalities. She was keenly observant, however, avidly attending dress rehearsals of other dancers. That was lucky for her when she inherited the lead role in La Chatte.

The slippery stage set for La Chatte (1927) downed two prima ballerinas – including Alice Nikitina shown here – before Markova inherited the role.

“[Olga] Spessivtseva created it and had an accident, and then [Alice] Nikitina took over and she hurt her foot, and then I went in,” Markova explained to Speaking of Diaghilev author John Drummond. “I was the third Cat. I was only sixteen at the time, but I was very observant. I had noticed that they complained so much about the floor because it was black. American cloth, terribly slippery in certain areas. And other areas, because of the very modern design, were like cotton, two surfaces, and I figured out that was causing the accidents.”

Making matters worse – or better, depending how you look at it – La Chatte choreographer George Balanchine decided to take advantage of Alicia’s special talents and add more complicated and difficult moves. Again, as told to Drummond: “I thought, I don’t want to hurt my foot. I don’t want to be put out, because it was a wonderful ballet, marvelous role. I had to solve the problem somehow, and this slippery floor, because otherwise I wasn’t going to be able to do all these double turns in the air that Balanchine had given me and all these pirouettes on pointe which he had added, so I suddenly remembered when I danced on a ballroom floor, I used to have rubbers [sole grips] put on my ballet shoes.”

As one critic noted, “The Cat of Alicia Markova was flawless. She is an accomplished ballerina . . . one of the greatest dancer talents of present times.” And resourceful. In fact, to solve an ongoing workout problem, she invented one of today’s most ubiquitous ballet essentials. The lightbulb went off while Markova was knitting a bed jacket as a Christmas gift for an elderly friend. In order to make the wrap both warm and comfortably lightweight, she created an airy, lace-like stitch using extra thick wooden needles.

That gave her an idea. Up until that time, dancers wore heavy leg warmers over knit tights during winter practice sessions. Despite the cold, the wool made them sweat profusely. In Markova’s case, perspiring heavily led to weight loss she could ill afford. So using the same open-weave stitch as in the bed jacket, she created lightweight leg covers that were breathable and less restrictive.

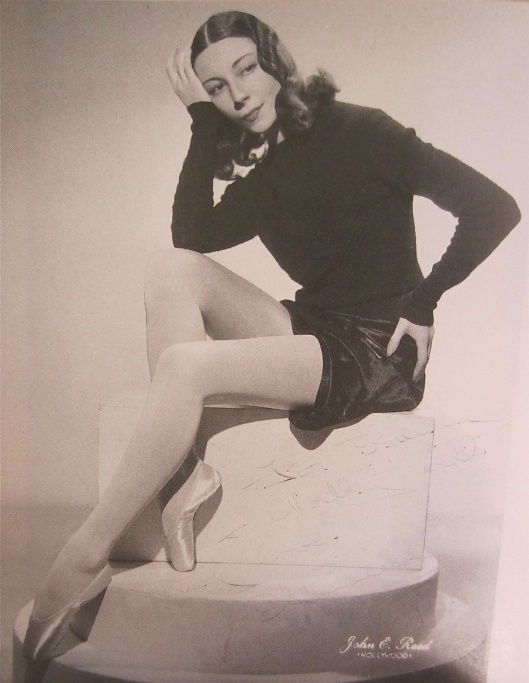

. . . leg warmers! (Here, taking a break from rehearsing at Jacob’s Pillow, 1941)

When fellow dancers saw Markova’s creation, they asked if she might be willing to knit them several pairs as well. She would. They quickly caught on and the ballet world has Alicia Markova to thank for the standard practice leggings of today.

Unlike many of her peers, Markova was always trying to put on weight rather than lose it. Bone thin in her early years, she was once described by dancer/choreographer Agnes DeMille as “the stringiest girl I ever saw, a darling little skeleton.” And as Ballet Club’s Marie Rambert noted, “Happy Alicia who can eat like a mortal and dance like an immortal. It was so astonishing to see Alicia putting down a thick solid steak and kidney pie, and to think when she comes on the stage, she’s a disembodied spirit. How did she do it?”

Five meals a day cost money and Markova made very little of that while pioneering British ballet in the early 1930s. “I had to live and I always had a great appetite,” she later reminisced. “I love my food, so I was doing commercial work as well.” The “commercial work” Markova referred to was dancing in popular stage musicals, as well as live at London’s Regal Cinema three times daily between film showings – much like the Rockette shows at Radio City Music Hall in New York. Frederick Ashton was the choreographer.

Paltry wages from London’s nascent ballet companies necessitated Markova’s taking on commercial work to support herself and her family. (Here in the romantic comedy A Kiss in Spring, 1930, with Harold Turner.)

From The Making of Markova: The pay was exorbitant for the times, £20 a week for Markova, and would subsidize her and Ashton’s more serious collaborations for the budding British ballet community. . . . Everything was on a grand scale, especially when compared to the tiny, small-budgeted Mercury Theatre. . . . Sandwiched between a performance of The Regal Symphony Orchestra and the Hollywood film Illicit – starring Barbara Stanwyck and Joan Blondell – Alicia Markova and William Chappell were to appear live on stage in the Dance of the Hours. The production was quite an extravaganza with the two leads, amply surrounded by a large – though rather inexperienced – corps de ballet. The audience was wowed nonetheless, captivated by the two stars, elaborate sets, and fanciful costumes. . . .

The Cinema production numbers changed every three weeks, which meant Markova would be performing three shows a day in one ballet, while rehearsing the next one. It took a toll physically, especially in Ashton’s Foxhunting Ballet, where Markova played the titled Fox “in all-over brown leotard, large bushy tail, a bonnet with little ears and paw-like gloves.”

Markova and Ashton’s commercial work helped popularize classical ballet to a wider audience. (Markova in Ashton’s La Péri at the Ballet Club, 1931.)

In 1945, Markova danced in Broadway’s musical/comedy The Seven Lively Arts to expose new audiences to classical ballet. (Captured by legendary caricaturist Al Hirschfeld here with Anton Dolin and comedians Beatrice Lillie and Bert Lahr.)

. . .”I just remembered being dazzled at what she was doing,” [ballet critic] Arnold Haskell remembered years later. “It was sandwiched between the selling of ice-creams and the film and all that, and you couldn’t get into a ballet atmosphere, but you could admire the virtuosity, and it was a show of virtuosity for a popular public.” In many ways, it could not have been a more effective tool for helping ballet trickle through all levels of society in England for the first time.

While many high-toned balletomanes looked down on a ballerina of Markova’s stature performing in such “mass-market” productions, she continued appearing in popular venues long after she needed the money. Never a snob, Markova felt exposing new audiences to the beauty of ballet – no matter where they first saw it – would only increase ticket sales for classical dance. And it did.

Another boon to popularizing ballet in the 1930s and ’40s was Markova’s appreciation for – and mastery of – the mass media of her day. In 1932, she became the first ballet dancer ever to appear on the new-fangled medium of television (see earlier post: The Television-ary Markova), and willed herself to become a more vocal marketer in newspapers and magazines. That was not easy for a woman who barely spoke a word until age 6 and totally lacked confidence as a public speaker. But Markova loved ballet, and wanted everyday folks everywhere to share her appreciation.  Understanding the power and wide reach of print media, she slowly but surely became a more lively and entertaining interview subject. Her natural empathy and down-to-earth manner endeared her to thousands of housewives and working women, especially during the war years. (See earlier post: Markova Entertains the Troops.)

Understanding the power and wide reach of print media, she slowly but surely became a more lively and entertaining interview subject. Her natural empathy and down-to-earth manner endeared her to thousands of housewives and working women, especially during the war years. (See earlier post: Markova Entertains the Troops.)

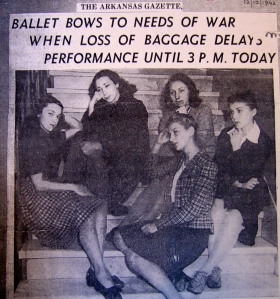

Contractual obligations necessitated Markova’s dancing in the U.S. during WWII, though she wished to stay in London with her family. (From left to right, the Marks sisters Vivienne, Doris, and Bunny.)

And speaking of the war years, Markova wished to remain in London with her family and friends at the outbreak of WWII. Unfortunately, she had an ironclad contract to dance in the U.S., with non-compete clauses and threats of legal injunctions requiring she honor her commitment or stop performing all together. As the main financial support of her sisters and widowed mother, Markova had no choice. But she managed to stay connected to her loved ones through weekly shipments of goods that were rationed in wartime London.

By splitting travel expenses with fellow prima ballerina (and best friend) Alexandra Danilova, Markova was able to send more rations and money home to her family during the war years.

That necessitated two things: careful budgeting of her meager wages, and inventive packaging to insure delivery. From The Making of Markova: “I would always ask what the shortages were and I remember the one time, they said lemons. . . . You couldn’t get lemons. I went out and bought a lot of lemons, and I thought how are we going to get them through? Customs will take them first, probably. So what we did, we got a whole lot of old sweaters that looked like awful old shabby things and filled the arms with the lemons and rolled them up . . . and we sent them over to the family.”

Though metals were severely rationed during the war, Markova shared her allotment of hairpins with the ballerina “bunheads” back home.

Markova also made sure to send “necessities” like hard-to-find lipsticks for her sisters, with ballet shoe ribbons and metal hairpins going to needy “bun heads” at the Sadler’s Wells Ballet School. “Bobby pins! We couldn’t get anything like that,” famed British ballerina Beryl Grey later told Markova. “We were so excited and grateful, and so touched that you were thinking of us.”

“An extravagance is something that your spirit thinks is a necessity,” proffered British philosopher Bernard Williams. One might agree that a fur coat is a prime example. But that wouldn’t be true for early 20th century ballet dancers. Winter tours throughout Europe, and later the United States, often required extensive journeys in unheated trains. It was a bone-chilling experience. In fact, Anna Pavlova caught pneumonia when her touring train broke down in a frigid snowstorm, causing her premature death within weeks.

Fur coats were truly a necessity for ballerinas during frigid cross-country tours. (Here, the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo trio of Markova, Danilova, and Mia Slavenska.)

When the 14-year-old – and penniless – Markova was accepted at the Ballets Russes, a generous, well-traveled friend of the family had one of her own fur coats cut down and remade for the tiny dancer, knowing she would need it. Later, Markova learned how valuable that gift really was. It wasn’t just the unheated trains. Dancers often spent hours on wind-swept, icy rail platforms waiting for luggage, costumes and sets to be loaded or unloaded. A lightweight fur also served as a soft mattress, warm blanket, and even a public relations tool. After lengthy trips on bumpy railcars, ballerinas hardly looked their best when arriving in a new town. Markova noted that donning their fur coats made them look glamorous to the press, even when they could barely keep their eyes open.

There was one “necessity” Markova staunchly opposed throughout her career. She was repeatedly advised to have her ethnic nose bobbed so she would look “prettier” – and more importantly – less Jewish.

When Markova began dancing, classical ballerinas were all Russian, and Jews were not allowed to attend the Maryinsky ballet school in St. Petersburg. In fact Jews weren’t even allowed to live in cities like St. Petersburg and Moscow without special permits. Anna Pavlova was Jewish, but hid that fact throughout her career. Even when she was world-famous, she was afraid of losing fans if her religion became public in such anti-Semitic times.

Alicia Markova felt differently. Not only did she refuse to have her prominent nose “fixed,” but she was also openly vocal about her religion, becoming a great source of pride in Jewish media circles throughout Europe and the United States.

Markova’s prominent profile was later celebrated by fashion magazines, such as this stunning Vogue photograph by John Rawlings.

Markova would become the first Jewish – and first British – prima ballerina assoluta in history, and a role model for young dancers all over the globe. “Necessity is the last and strongest weapon,” wrote Titus Levy in ancient Rome. For Markova, honoring her religion was that kind of necessity.

Markova would become the first Jewish – and first British – prima ballerina assoluta in history, and a role model for young dancers all over the globe. “Necessity is the last and strongest weapon,” wrote Titus Levy in ancient Rome. For Markova, honoring her religion was that kind of necessity.