Tags

Alicia Markova, Anton Dolin, Ballets Russes, English National Ballet, Frederick Ashton, Lean In, Leigh Thomas, Margot Fonteyn, Ninette de Valois, Sergei Diaghilev, Sheryl Sandberg, The Guardian, The Royal Ballet

She can if her name is Alicia Markova. Though Sheryl Sandberg certainly didn’t have ballerinas in mind when writing Lean In: Women, Work, and the Will to Lead, she’d be mightily impressed with Markova’s work ethic and hard-won success. Yes, even ballet could be a ruthless profession controlled by men, and Markova fought for a seat at their table. Though painfully shy and obedient as a child, Lilian Alicia Marks grew up to be not only the greatest classical ballerina of her generation, but also a force in ballet. She pioneered British ballet at a time when only Russian troupes commanded respect and full houses; and two of the three companies she helped launch are still in existence today – The Royal Ballet and English National Ballet.

By becoming the first British-born international ballet star, Markova paved the way for countless dancers to follow. One was a young girl named Peggy Hookham, who Markova took under her wing and mentored. Hookham is better known today by her more mellifluous stage name, Margot Fonteyn. Later in her career, Fonteyn paid tribute to Markova saying she “always remained my ideal and my idol.”

Women working together to succeed would also please Facebook COO Sandberg. Markova had the good fortune to have her own female mentor, the beautiful Irish-born ballerina Ninette de Valois (christened Edris Stannus). When Markova was a timid 14-year-old neophyte at the Ballets Russes, company impresario Sergei Diaghilev – who thought of Alicia as a daughter – asked the self-assured de Valois (then 26) to watch over his “Douchka,” (little darling). Markova couldn’t have been more fortunate. Years later, she offered her public gratitude in a radio tribute celebrating de Valois’s 100th birthday (she lived to be 102!): “I was put in your care and I thanked God every night because it wasn’t so much the dance part, but how you taught me what I should eat, what would be good for me, what would give me strength. Not only that, but how to go shopping and how to buy everything, because at that time, we all had very, very low salaries. And so really, in a few words, you tried to teach me how to deal with life.”

And it would be the pairing of de Valois and Markova that launched the Sadler’s Wells, known today as The Royal Ballet. The formidable de Valois was convinced she could form an all-British ballet company using her talents as a choreographer, teacher, and director. What she lacked was a star. Markova would become the first British prima ballerina to perform many of today’s most famous full-length Russian classics (Giselle, Swan Lake, The Nutcracker), putting de Valois’s fledgling company on the map. In her autobiography Come Dance With Me, de Valois wrote the following about her lifelong friend who she always called Alice:

“I think of all the artists that I have ever encountered she is the most self-reliant. Her strength of purpose and her courage run deep: when Alice says very quietly that something does not matter, that it is quite all right, she means, in one sense, exactly the opposite – for she does not trouble to explain that she considers it her own concern to set about rectifying the matter in question.”

Under de Valois’s tutelage, Markova learned to stand up for herself, and never shied away from asking for a higher salary – another Sandberg rule. When first partnered with Markova, the inexperienced choreographer Frederick Ashton was so impressed with her negotiating skills that he asked her to handle his salary dealings as well. But money was never the driving force in Markova’s career. She only asked for what she thought fair, and took less money than she could have received from large established companies in order to remain loyal to de Valois and their joint efforts to legitimize British ballet. Even more remarkable was Markova’s gutsy decision to become the first “free agent” prima ballerina in later years, an unheard-of choice when prima ballerinas remained with one or two companies throughout their entire careers.

As the London News Chronicle said of Markova in 1955: She is to the dance what Menuhin is to music, but unlike the violinist, she has no competitors in her field, for all the other leading ballerinas, from Fonteyn to Ulanova, work in the framework of established companies. Indeed, it seems as though Markova may be the last of her kind—the “rebel” dancer who is prepared to carry the full responsibility for her career on her own delicate shoulders.

It meant far more work, but also complete freedom, enabling Markova to pursue her dream of bringing ballet to people everywhere. She became the most widely traveled dancer of her era, performing in parts of the world that had never seen any ballet, let alone one of its greatest practitioners.

As a freelancer, Markova became a de facto CEO, handling her own bookings, finances, and travel arrangements, as well as hiring dancers, costume designers, and musicians. It was a tall order for someone who devoted her life to perfecting her art, and something she kept hidden from the public. Markova feared that being known as a smart business woman would take away from her ethereality on stage.

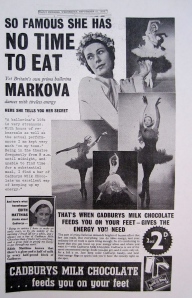

This week in The Guardian, former ballet dancer Leigh Thomas discusses how her ballet training was the ideal preparation for becoming a CEO in the advertising business world that she works in today. Markova was also a brilliant marketer, as you can read in a former post: Markova Strikes Up the Brand.

For the British dance pioneer, generating “good copy” was not about self-aggrandizement. Popularizing her art form was Markova’s passion, and one she most certainly leaned in to. She would become the most highly paid prima ballerina in the world, the most famous, and a groundbreaker at every turn. Of course, her profession called for a little leaning on as well!