Tags

Alicia Markova, American Ballet Theatre, Antony Tudor, Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, Bette Davis, Edwin Denby, Giselle, Hollywood Canteen, Hugh Laing, Humphrey Bogart, John Garfield, Lauren Bacall, Leonide Massine, Lisa Mitchell & Bruce Torrence, Marlene Dietrich, Mickey Rooney, Pearl Harbor, Rita Hayowrth, Romeo & Juliet, Sol Hurok, Stage Door Canteen, To Have and Have Not

Seventy-two years ago today the Japanese bombed the United States Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor in Oahu, Hawaii. Over 2,400 people were killed – sailors, soldiers, civilians – and nearly 1,200 wounded. Within an instant, the United States was at war. At the very moment Pearl Harbor was under attack, prima ballerina Alicia Markova was in New York City dancing a sold-out matinee performance of Giselle. The audience would hear the horrific news at intermission. When they silently returned to their seats for Act II, the poignancy of Markova’s performance brought a flood of cathartic tears.

The British dancer would spend the next three years supporting the American war effort in every way she could: raising money and donations, entertaining the troops, and offering a brief escape from the world’s worries. “Little 96-pound Alicia Markova, who admits her heart is tangled up with an Englishman now making uniforms for the R.A.F., thinks the ballet has a definite war mission,” revealed a Philadelphia newspaper. “‘Escape,’ she says . . . ‘and it’s good in time of war.'”

When the U.S. entered World War II on December 7th, 1941, Markova’s homeland of Great Britain had been under siege for over two years. She had wished to remain in London to be with her family and loved ones, but was contractually obligated to dance in the United States with the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo. Impresario Sol Hurok threatened legal action to prevent her from performing anywhere if she refused to go. As Markova was supporting her widowed mother and sisters, she had no choice.

Though dancing in the U.S. brought solace to the celebrated ballerina, worries about her family and friends were omnipresent. “Mr. Massine [artistic director Léonide Massine] won’t allow newspapers in the studio,” Markova told a newspaper reporter in 1940. “And a good thing, too. I was trying to take my mind off what I had read at breakfast one morning. Suddenly one of the corps de ballet opened a paper. ‘London Bombed!’ I felt quite sick. I forgot my entrance and things got pretty blue. . . . The knowledge that your country is at war, that your family is in it, is always with you. While working you can get away from it for a few moments.”

The news only got worse, as Markova told another interviewer in January 1941: “I picked up the newspapers the morning after my New York debut in ‘The Nutcracker.’ In one hand I held the most wonderful compliments from the critics – and in the other, a cable from my mother, telling how a bomb had gone through our apartment. Fortunately,” went on the soft-voiced star of the ballet, “my mother and three sisters were away at the time.”

Throughout the war, wherever she was performing, Markova made time to visit Stage Door Canteens across the country. The lively nightspots offered wholesome evenings out for enlisted men and women (no officers!), with free food and the company of cheerful volunteers. Some were rather famous, especially at the Hollywood Canteen founded by actors Bette Davis and John Garfield. (“No liquor, but damned good anyway,” reported one sailor.) Markova had a fine time socializing with the American G.I.s: pouring coffee, chatting amiably, and tripping the light fantastic. The ballerina taught ballroom dancing to the servicemen and they in turn showed her how to jitterbug.

To entertain G.I.s, Markova jitterbugged with Mickey Rooney. (Photo from The Hollywood Canteen, an entertaining book by Lisa Mitchell & Bruce Torrence.)

Markova became so adept that one night she entertained the troops by jitterbugging with film star Mickey Rooney; but an over zealous G.I. named “Killer Joe” almost did her in with his exuberant dance moves. Markova loved it all, and so did the countless grateful soldiers who sent her thank you letters and requests for photos. The bone-thin ballerina couldn’t believe anyone would consider her “pin-up girl” material! But Markova managed to touch the soldiers’ lives in a very different way than Hollywood glamour girls like Rita Hayworth.

Performing for departing or wounded soldiers, Markova’s magical stage presence was an unforgettable experience that lived long in one’s memory. Headlines in many newspapers spoke of her power to enthrall servicemen with classical dance: “Ballet Their Escape From War Jitters,” read one; “Ballet Hailed as War Outlet” read another. And Markova always made time to sell war bonds while on tour, once even appearing on the radio in the window of I. Magnin’s department store.

Markova also supported the women that the soldiers left behind. From The Making of Markova: She was willing and able to put herself in the place of average American women whose lives had changed drastically after the Untied States entered the war. Not only were their loved ones drafted, but in a way, they were too. Women who had never held jobs in their lives were needed as factory workers and fill-in employees for all the men now overseas. Many were scared, tired, and feeling neglected. Markova was a Jewish woman at a time when her religion had horrific consequences. She knew what it was like to feel insecure and afraid. And that attitude won her many female fans.

Her interviews were filled with practical beauty and health tips to make women feel better in those tough times. It was hard to feel attractive while doing factory work. Markova knew how happy her sisters were to receive her care packages of lipsticks and nail polish, which they were unable to get in war-torn England. And Markova always reserved some of her war rations for friends back home, sending weekly food packages and much-needed supplies. Thanks to Markova’s parcels of metal hairpins and ribbons, the corps members at London’s Sadler’s Wells Ballet (today’s Royal Ballet) were able to remain”bunheads!”

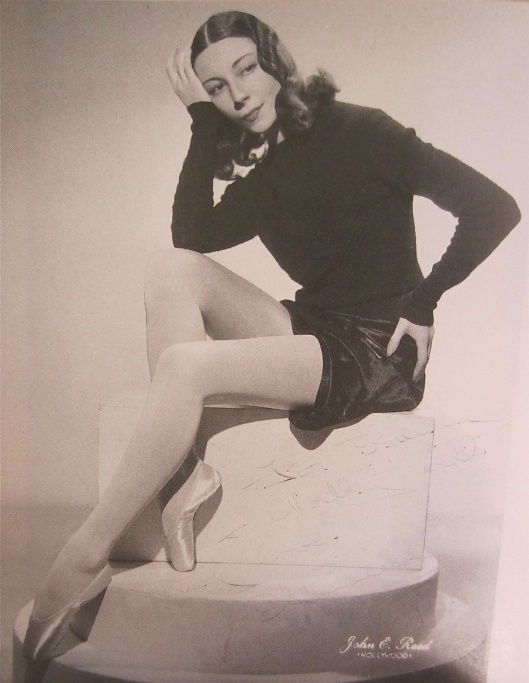

Markova also understood that times of war required restraint in appearance. “Miss Markova is not, she insists, a glamour girl,” reported the New York World-Telegram. “She’s a simple, quiet English girl who happens to be a good dancer. Her press agents have asked her to dress more snakily, let down her hair and throw off her natural reticence. But Miss Markova insists that being herself and a good dancer into the bargain is ‘Quite Enough.'”

The quietly chic dancer still managed to set fashion trends. Out to dinner in 1941 with friends from the Ballet Theatre (today’s American Ballet Theatre), Markova was photographed wearing a beret and fitted houndstooth suit with padded shoulders, nipped in waist, and knee-grazing hemline.

Three years later, 19-year-old Lauren Bacall would wear an almost identical outfit in her first film, To Have and Have Not. Though female movie-goers loved the fashions, far more memorable today is Bacall’s repartee with soon-to-be-husband Humphrey Bogart: “You don’t have to say anything, and you don’t have to do anything. Not a thing. Oh, maybe just whistle. You know how to whistle, don’t you, Steve? You just put your lips together and… blow.”

Markova got her share of whistles too, accompanied by standing ovations at curtain calls across the country. The popularity of ballet actually increased during the war years, as famous American dance critic Edwin Denby explained: “Wartime, here as abroad, made everyone more eager for the civilized and peaceful excitement of ballet. More people could also afford tickets. And in wartime, the fact that no word was spoken on the stage was in itself a relief. Suddenly the theaters all over the country were packed.”

In order to accommodate audiences nationwide, the company practically lived on trains. Outside of the big cities, performances were often one-night stands held in odd venues such as high school gymnasiums, American Legion auditoriums and Town Halls. As Markova recalled, “Just before we were leaving the Metropolitan (Opera House in New York), the list – the tour list – went up, and I remember looking at the list and I couldn’t understand it because for three whole weeks we never slept in a hotel.” Fortunately Markova was adept at sleeping on trains, and she laughingly remembered inventing “the Army Game” so the company could bathe. The wily “maneuver” involved taking advantage of hotel day rates while the stage crew unloaded and built sets. One dancer would check in to a single suite, with six more sneaking up afterwards. They would tip the maid to bring extra towels and take turns bathing, eating, and napping. It was like a Marx Brothers movie!

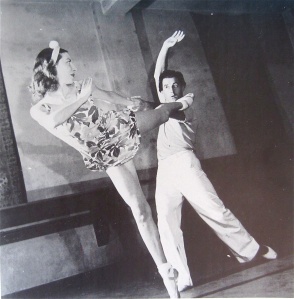

For the Ballet Theatre’s British contingent, mastering new choreography helped take their minds off war worries back home. Antony Tudor’s Romeo & Juliet co-starring Hugh Laing (with Tudor as Tybalt) was one of Markova’s most rewarding roles. Though 32 years old when the ballet debuted in 1943, she had no trouble embodying a love-struck girl of 14. In preparation, Markova memorized the entire Shakespeare play so she would have Juliet’s thoughts, words, and actions in her head as she danced.

“Her new Juliet,” wrote Edwin Denby in the New York Herald Tribune, “is extraordinary. One doesn’t think of it as Markova in a Tudor part; you see only Juliet. She is like no girl one has ever seen before. She is completely real. One doesn’t take one’s eyes off her, and one doesn’t forget a single move.” Added dance critic Grace Roberts, “For once, there was a Juliet who made Romeo’s quick reactions believable. Her light darting steps barely seemed to touch the ground . . . Markova’s deer like shyness in the first scene, her tragic controlled despair, her exquisite movement of her hand as she wakes up in the tomb scene, are all unforgettable in their subtlety.”

For the transported audience, it was indeed an escape from the worries of the world.